Crossing Over: How Art Market Expertise Can Enrich Museum Teams

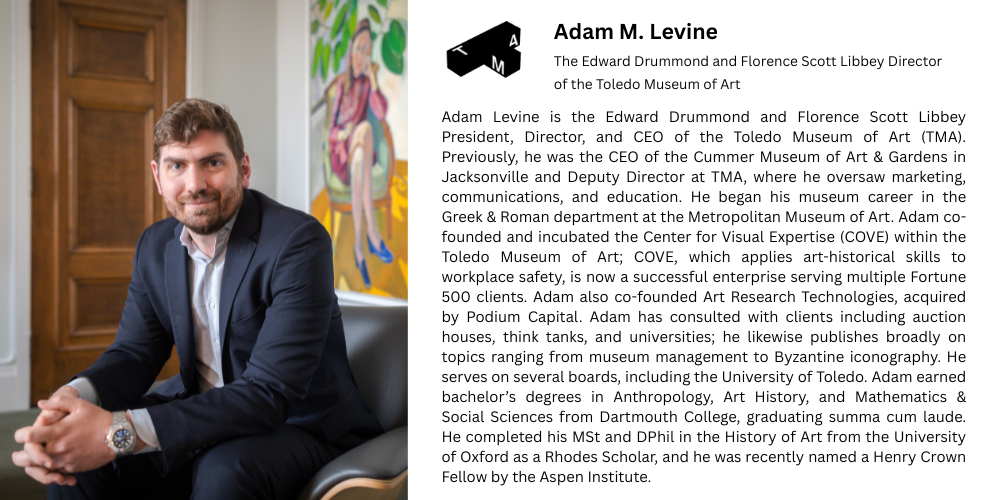

A four-part series on evolving museum talent by Adam Levine, the Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director of the Toledo Museum of Art

In the first article of this four-part series,[1] I suggested that art museums would do well to consider candidates from the commercial art world for museum directorships. My argument was not that this is the only underexplored pool of art world talent—it may not even be the best—but the skills required for success in both domains are similar. That argument is extendable more broadly: Individuals with art market backgrounds could make for great employees in a range of management and leadership roles across museums. Most obviously, given fraying museum finances and the evident cracks in public support the world over, it would be sensible to consider candidates with experience in building revenue streams in art services, which remain relatively underutilized in the art museum business model. However, having a senior level leader with a background in the commercial art world would round out the diversity of perspectives on any team, helping get to better decisions on a range of different topics.

There are well-known problems with the so-called ‘business case for diversity,’ including that it subordinates the overall value of diversity to economic outcomes.[2] However, precisely because diversity is good per se, it also benefits companies in ways that the ‘business case’ literature has validated repeatedly over decades. In a survey of multiple studies on the topic, Forbes reported that ‘diverse-led organizations are’[3]:

- 39% more likely to outperform those lacking diversity

- 12x more likely to engage and retain employees

- Nearly 8.5x times more likely to inspire a sense of belonging

- 8.5x times more likely to satisfy and retain customers

Over the past few years, museums rightly have been focused on expanding their recruitment networks, committing to a culture of belonging that increases retention, and in so doing, building a workforce that better reflects the communities they serve. This makes eminent sense. A museum staff more reflective of its audience will more likely achieve a mission of engagement (see the first article in this series) since the staff will reflect the perspectives and expertise of its community. Similar logic, though, can be extended to other technical domains.

The key reason that diversity confers such strong business benefits is that it helps expand thinking and catalyze innovation. A diversity and innovation survey by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) in 2017 found that companies with above-average diversity scores generated almost twice the innovation revenue of those that had below-average diversity scores.[4] Whether diversity is considered in terms of demographic characteristics or backgrounds, the results remain the same: Teams comprised of people with similar goals but orthogonal thinking develop newer and better ideas, which helps organizations thrive.

Greater porosity between the commercial art world and the museum world would confer similar benefits. Beyond the obvious opportunities for art market participants to leverage their know-how and networks in art transactions, the speed with which the commercial sector operates, the suppliers with which one partners, and even the type of programming museums do could all benefit from a market perspective. Museums must maintain scholarly standards, but in the ‘culturally omnivorous’ world LaPlaca Cohen’s CultureTrack survey identified more than a decade ago—one in which an overriding motivation for people’s cultural participation is to ‘have fun’—it cannot hurt to have an additional perspective that is on trend and knows how to meet market demand.[5]

There are many managers and leaders known to this author who have moved from auction houses and galleries to museums in fields ranging from curatorial to marketing to fundraising. Consider the following case study, left anonymous for the sake of the individual’s identity, as just one example: A major global museum, one that is large enough to have multiple curatorial departments each with its own fundraising support, hired a development officer with commercial gallery experience in the same segment of the art market for which she now fundraises. This individual comes not only with passion for the subject, but with knowledge of the collectors, an understanding of their net worth from things she had sold them previously, and valuable insight into which artworks are owned by which (potential) patrons.

Transitions from the art market into the museum profession currently happen fortuitously rather than as part of a concerted effort to broaden the museological talent pool. In order to validate the investment required to build a more systematic and intentional recruitment process, though, it would be helpful to have a sense of interest among market participants in making the switch to museums. In the next installment of this series, we will report on the results of a field-wide survey being undertaken by the Sophie Macpherson research team to assess just how much appetite there is. There may be more than you think.

Works Cited:

[1] https://www.sophiemacpherson.com/setting-the-scene-talent-leadership-in-todays-museums/

[2] https://hbr.org/2022/06/stop-making-the-business-case-for-diversity

[3] https://www.forbes.com/sites/juliekratz/2024/06/26/why-are-we-still-talking-about-the-business-case-for-diversity/

[4] https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/how-diverse-leadership-teams-boost-innovation

[5] https://s28475.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CT2017-Topline-Deck-1.pdf